Last week’s Prime Minister’s Questions (and the week before that… and the week before that…) showed that you don’t need to put your watch back an hour or take a stroll in the cold to work out that winter is on its way. Just turn on your TV- like clockwork, the energy debate is back on the agenda, and this year it’s heating up more than ever.

In a scene reminiscent of a criminal line-up, last week the ‘Big 6’ energy companies filed in to face the Energy and Climate Change Committee for cross-examination. They were questioned on wholesale prices, the effects of green levies, internal costs, supply and network demands, and the announcement by four of the ‘Big 6’ companies of average price rises of 9.1%.

I would excuse the overload of courtroom imagery, except that on this occasion, it really did feel like the energy companies were on public trial. By the looks of the announcement by the Energy Secretary Ed Davey – outlining plans for a competition commission for the energy market, and a review into energy competition (to add to the 17 reviews between 2001 and 2010 alone) – this trial won’t be over any time soon.

Energy prices have always been a useful political balloon for the winter months, buffeted between the parties when the political gains are visible. But when Ed Miliband announced a 20 month energy price freeze in September at the Labour conference as his headline election policy, and one month later four energy companies announced 9% price rises, the debate shot up the agenda. It certainly gave Ed Miliband a good post-conference poll boost. But for British-owned energy companies Centrica and SSE, the announcement saw their share prices tumble. This might not ordinarily concern the general public, but these companies provide thousands of UK jobs and training opportunities, and given the (mostly) stable nature of utility share prices, many pension funds and investments are also held in utility shares like these.

There are two main difficulties with throwing an issue like energy policy right in to the centre of the political domain.

The first is that it is fairly complicated to explain in a nutshell. It is therefore very easy for the public to jump on the populist bandwagon (say, freezing prices for almost two years) without understanding the nuances of how much profit energy companies actually make and how that profit is divested. And the second problem is that is becomes so interconnected with other issues that the conversation inevitably lands right back on the doorstep of traditional party ideologies.

So, let’s look at the figures.

Energy companies have certain unavoidable overheads, like any functioning business. This includes staffing and internal expenditure, network and operating costs (such as pipeline and storage repairs, and transporting the fuel), and taxes including corporation tax and the much-cited green levies. Stinging fines such as Ofgem’s £10.5 million fine to SSE in April after sales staff mis-sold gas and electricity tariff savings, also increase their outgoings. Then they actually have to source the fuel.

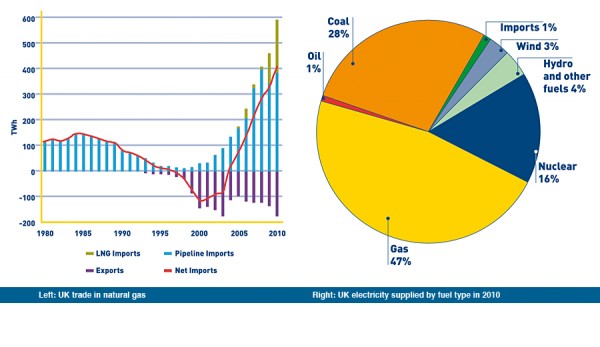

As a nation, we are doing increasingly badly at supplying our own energy. Cuadrilla- the company leading the charge to explore the UK’s shale gas reserves- points out that since 2004 the decline in gas production in the North Sea, coupled with the UK’s increasing reliance on gas for meeting its energy needs, has resulted in the UK becoming a net importer of gas supplies. Energy giant Centrica predicts that by 2020, the UK will be importing 70-80% of the gas it needs. Given that in 2010, a whopping 47% of the UK’s energy needs were met by gas, this decline in domestic production is particularly worrying.

Coal- our second biggest energy source for electricity- is another industry in decline in the UK. Figures from the Department for Energy and Climate Change show that out of the 64.1 million tonnes of coal that the UK consumed in 2012, only 16.8 million tonnes was produced in the UK (9.9% less than the previous year), and the rest was imported. Furthermore, whilst Germany continue to increase their coal production, the former Labour administration’s commitment to reducing the UK’s carbon footprint means that UK coal operations now need to close by around 2019. Unless we reduce our reliance on coal as an energy resource, the UK will therefore be ever more dependent on overseas energy supplies.

In fact, in 2011 the Office for National Statistics and the Department for Energy and Climate Change released a joint UK energy summary where they acknowledged that ‘in 2011, imports of energy exceeded UK production, the first time this has happened since 1974.’

(photo source: Cuadrilla website- http://www.cuadrillaresources.com/benefits/energy-security/)

This leaves the UK in a position where we have a declining ability to control the baseline prices of energy.

On top of that, like any business an energy company has to a) maintain its current operations (such as making expensive repairs or replacing antiquated machinery), b) expand (building new, more technically-advanced sites and investing in advanced techniques for energy sourcing and extraction), and, most controversially, c) turn a profit. Chief Executives have to combine all of these pressures in to devising energy prices for customers that can maintain and increase their market share without losing droves of dissatisfied customers, whilst also answering to their shareholders by turning a healthy profit.

Furthermore, when new ideas for energy supply are floated, they often meet resistance from environmental groups and local campaigners. PR firm Bell Pottinger got caught in the crossfire recently when opponents of their fracking client Cuadrilla vandalised their London offices. And an announcement of a new nuclear power plant in Hinckley has enraged anti-nuclear campaigners.

More energy diversity and supply could well be the ticket to lowering energy prices- for suppliers at wholesale level, and for consumers (In the US, Cuadrilla assert that the exploitation of shale supplies over the last 10 years has helped to bring consumer energy prices down by around a third). But new energy solutions are proving yet another political quagmire for the party leaders to wade in to.

Quite rightly, these difficulties don’t excuse pure extortion. Some firms such as E.ON have admitted that the company they buy energy from- the wholesaler- is in fact owned by the same parent company as they are (although they maintain that the supplier and wholesaler businesses are completely separate). In these cases, it is more difficult for consumers to understand why suppliers are paying such a high wholesale price when an internal deal could be struck to reduce energy bills.

Essentially, though, it comes down to the same argument- they are businesses. Energy has a high market value, and selling it for less than it’s worth is, for a business, a pretty ludicrous idea.

In addition, contention between Ofgem’s figures and the figures provided by energy companies continues to fuel this debate on wholesale prices. Whilst energy companies maintain that price rises have been necessitated by an average 4-8% rise in wholesale prices, Ofgem suggests that wholesale prices have only increased by 1.7%- around £10 extra on an average household’s £600 energy bill. These disagreements make it even harder for consumers to ascertain whether energy company price rises are genuine or inflated.

This week, using new figures from Ofgem, the BBC put together a handy pie chart to illustrate the price breakdown of the average household bill, and the results are surprising;

(photo source: BBC website- http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-24706306)

The fact that 46% of an average fuel bill is made up of the wholesale price of the energy product is high, but not altogether unexpected. But the realisation that energy companies pay about the same in VAT as they receive in overall profit is a figure that isn’t paraded nearly enough in the mainstream media. And of the money they take home at the end of the day, some of this is also then reinvested in to improving the business.

This complicated and interconnected energy landscape is therefore an incredibly difficult policy maze to navigate. But has anyone actually got any bright ideas, or is this all just a lot of hot air?

Sir John Major certainly jumped in head-first, when he suggested a windfall tax for energy companies to subsidise the high bills. Critics pointed out that this might drive energy investors overseas. Ed Miliband continues to champion his idea for a 20-month energy price freeze. Opponents point out that energy companies would have to raise prices accordingly both before and after the freeze to make up the shortfall.

Tax cuts, green levies, enforced competition; all of these ideas are bandied about, and what this week’s Prime Minister’s Questions highlighted is that every year the issue ends up boiling down to the same party divides. Conservative traditionalists hope that the natural fluctuation of market forces will bring competition to the fore and eventually drive prices down organically. Labour hardliners believe that bringing the state in- or, once the 20 month price freeze expires, an independent regulator- to control the market will force energy companies to bring their prices down. Sadly it would appear that, regardless of political ideology, until the UK reforms its own energy sourcing and production, the only way for prices is up.